...and how it relates to reference management

During an internship at my university library, I used to lead training courses on a particular reference management program. Invariably, when participants saw just how easy it was to automatically import references from databases or catalogs and then take that information and create a bibliography – and that all in a matter of seconds – all eyes would light up, and someone in the room would say, “It’s magic!”

Of course, it’s not due to magic at all, but something much more down-to-earth and rather dull sounding: metadata.

What is metadata?

Metadata is, as you would guess, data about data. It’s the descriptions librarians, publishers, database indexers, and web creators give to sources, such as books, journal articles, and websites. Although the term “metadata” is from the 20th century, the concept has been around as long as humans have attempted to organize physical items and knowledge with the goal of making them easy to find again.

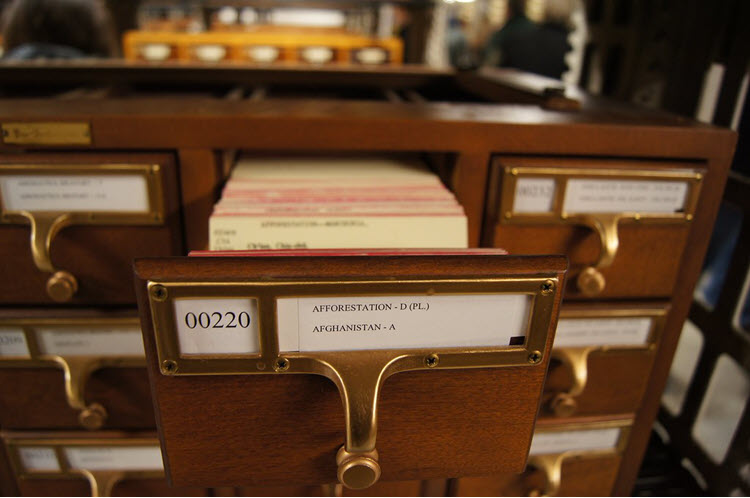

For example, the entries in early subject catalogs of books in a monastery library can be thought of as metadata. Later on, libraries began using card catalogs. Each card contained basic information about the book, where to find it in the library, and its main topics. The cards were organized by author, title, and subject, making it possible for library users to easily find items. Although card catalogs have long since made way for online catalogs containing much more information, the basic goal is still the same: the user should be able to find a relevant book by searching for its topic or some other information about it.

Although librarians used to be one of the only groups of people giving much thought to metadata, that’s no longer the case. In fact, today you might say that we live in the Age of Metadata. Many of us constantly use metadata in our daily lives.

When you search for something in Google, the search engine checks the descriptive information in the metatags of the webpage in addition to the actual text on the page. When you add hashtags to a photo you upload to Instagram, you’re adding metadata to it that helps other users find your picture. Because of metadata, you are able to quickly find songs by an artist you like when searching a music streaming service, such as Spotify. When you use a hotel booking service and filter by how close it is to the center of town and how expensive it is, you are able to do so because the database behind the page has metadata saved for each hotel.

How does metadata work?

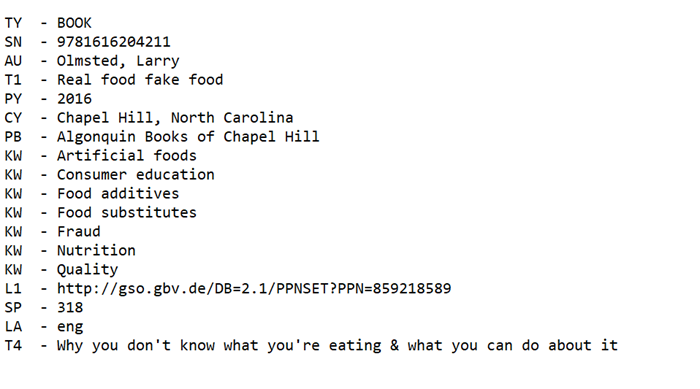

For metadata to be useful for information retrieval (as in the examples above), it needs to be entered consistently and in a structured format. This makes it possible to be easily used by a computer program or app. For example, reference management programs can import database results as long as the information is in a tabular format it can read, such as RIS format. Here’s an example of some of the information that you might find in a RIS file:

The abbreviations on the left are the field designations and the information on the right is the value. When you import a RIS file, the reference management program uses a mapping that tells it which RIS fields correspond to which fields in the program. Using that, the software pulls each value from the RIS file and places it in the matching field in the reference management program. It’s simple, but very effective.

Besides RIS, there are a number of other formats that function the same way. When a program such as Citavi is able to automatically import information for a book or journal article, it's because it uses an identifier, such as an ISBN or DOI, to perform a database search and then import the information from one of these formats.

Basic information about a source is a relatively straightforward type of metadata. For example, it’s usually very clear what the title of a book is, when it was published, and who the author is because you can see that information on the book itself.

But what if you are trying to describe the contents of an item?

That’s a much more subjective process.

You’ll need to decide which categories or keywords fit best and how detailed, or “granular” the description should be. For example, if you post a picture of your chihuahua on Twitter and only use the hashtag #dog, and someone else searches for the hashtag #chihuahua, they won’t find your picture. The same thing can also happen with synonyms. For example, #wienerdog and #dachshund refer to the same breed of dog but are two different hashtags. To get around this problem, many research databases and library catalogs use what’s known as "controlled vocabulary" to ensure that when someone searches for a synonym, they will find the same results they would have gotten by searching for the other terms.

Like vocabulary in general, controlled vocabulary can change over time. As cataloging policy specialist Lynn M. El-Hoshy writes, library subject headings, “are rich sources for tracking shifts and trends in terminology over the century” because they “serve as standardized labels for indexing the contents of library materials and reflect societal concerns and the language generally used to express them.” For example, a subject heading for books on cars in a library classification system might have initially been “carriage, horseless”. Later as the term “automobile” became more widely used, the heading would have been changed. Likewise, terms for new concepts constantly need to be added, for example if a new medical treatment is discovered.

Is there such a thing as too much metadata?

In the past, metadata was often limited to what could fit on catalog card. In the digital age, that’s no longer a concern; there’s no real technical limitation to the amount of metadata that can be created for a particular item. However, this can lead to its own problems. For example, journal articles in databases often have many keywords associated with them. If you import the articles into a reference management program, you’ll soon end up with hundreds of keywords, many of which may not be relevant to your research project topic. These unnecessary keywords can be distracting and slow you down if you're looking for a specific keyword later on.

The problem is not limited just to information you import. When you work with reference management software, you become a creator of metadata yourself. While it can be tempting to add as much information to each source as you can, just in case you need it later on, this takes up a lot of time that might be better spent actually reading your sources or writing your paper. So, instead of describing a source to death, try to focus on the metadata that is most relevant to you now and what is likely to be useful for you in the future should you ever need to use a source again.

Naturally, you’ll need to have all the basic citation information necessary for creating your bibliography later on. Here it’s important to double-check data that you’ve imported from other sources against the actual full-text article or book. Metadata is added either by people or computer programs, and mistakes do occur.

Beyond the details you need to cite your sources, think about what else is important to you. For example, you might want to assign categories or folders to help you better differentiate which source pertains to which topic. If you’re working with Citavi, you can even categorize pieces of information you find during your reading, for example, if you read a statement that you later want to quote word-for-word in your paper.

Ratings, keywords, groups, abstracts, tables of contents, evaluations, comments, summaries, notes, and call numbers in a library are just some of the many other options you might have in your program. Take some time to watch the how-to videos or read the guides for your reference management software so you can decide which options you have and which you want to use.

With the metadata you gather, you can do many practical things, such as creating a reading list containing your own comments for a book club, generating a bibliography for your paper with a click, or sharing useful sources with a colleague somewhere else in the world. It may not be magic, but metadata makes many tasks in modern life a whole lot easier.

What metadata do you like capturing for your research projects? Have you ever had a metadata import that was completely incorrect? We’d love to hear about your experiences on Facebook!

About Jennifer Schultz

Jennifer Schultz is the sole American team member at Citavi, but her colleagues don’t hold that against her (usually). Supporting research interests her so much that she got a degree in it, but she also likes learning difficult languages, being out in nature, and having her nose in a book.